By Vashti Farrer

It being wartime, and flats hard to find, Sally and her mother share with her aunt and grandmother. Their flat is down one side of an old building, near Kings Cross. It’s painted cream and brown and it peels a bit. Heavy curtains and ugly blinds cover the windows and dark, creosote blackout paper is stuck to the glass doors.

Her aunt and mother share one bedroom, Sally and her grandmother the other. Her grandmother spoils her with lumps of brown sugar from the ration jar. She pastes pictures of animals on a wastepaper bin for Sally and makes her a patchwork nightie from scraps of material. Sally’s favourite is the pale blue, satin patch near the hem. She finds it at night and rubs it with her big toe, while she sucks her thumb and stares through the dark at a tiny tear in the blackout paper. It’s a secret, because the tear looks like a fox’s head and only Sally knows it’s there. When she has the patch, her thumb and her fox, she feels safe. Even in the dark.

When Sally was a baby, she would crawl into the other bedroom and sit behind the curtained wardrobe, feeling the softness of her aunt’s evening dresses. Her aunt is good at sewing and makes them all herself. Some of the scraps have ended up in Sally’s nightie. Her mother doesn’t sew dresses, she embroiders, so Sally’s daytime dresses have cats and flowers on them.

Her aunt Bobo is glamorous. She looks like the film star Loretta Young. She works as a female mail sorter at the GPO and wears dresses in olive green, navy, or brown with shoulder pads and underarm protectors. She draws perfectly straight lines up the back of her legs to look like stocking seams. But at night, she turns into a butterfly and wears one of her pretty dresses to parties.

Sally’s parents divorced when she was a baby, so her mother works to support her. She tried to join the Land Army, but they wouldn’t take women with children, so she tried a munitions factory, but as an embroiderer she was too slow for the work so now she’s a tram conductress. She wears a uniform and cap, black lace-up shoes with socks. Sometimes Sally plays tram conductresses and calls ‘Fares please!’ and tears off pretend tickets. Once her mother tried to get a drunk man off her tram at the end of the line, so he woke up very cross, shouting, ‘I was only asleep!’ Another time, some American soldiers kidnapped her because they had to find a tram conductress for a treasure hunt, but she managed to persuade them to let her go or she’d lose her job.

Each day, Sally sees soldiers in the street, Australians, Americans and sometimes the Yanks have a girl on their arm, but Sally’s grandmother has said, ‘Nice girls don’t go out with Americans.’

That changes the day her grandmother goes to Randwick races. She catches the early toast-rack tram in time for the first race and is due home after the last. But she’s late; 6 o’clock, 7, 8 o’clock come, before they hear her key in the lock. Then her hat comes sailing into the lounge room and she announces, ‘I’fe bin drrrrinking gin. Wiv some Amerrricans. A Cnnl to be precissse,’ and the embargo is lifted.

In time, Sally’s aunt goes out with a lieutenant called Stanton. They share an interest in books, and he gives her his copy of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Suicide Club, with his name J.R. Stanton written inside. She keeps it for the rest of her life. From time to time, an orchid appears in the fridge in a clear florist’s box and her aunt now wears nylons sometimes instead of drawing pencil seams.

Her mother meets a sergeant named Briggs. He can shoot two sixpences in mid-air and is working on shooting three. She is impressed but suspects he might have been a gun runner in Acapulco. He makes her sweetheart jewellery – a locket from a curved florin piece with his photo inside and a charm bracelet of threepences. Her mother never wears them out because she tells Sally, ‘It’s illegal to deface the currency.’ When they become engaged, he gives her a photo of his family, who are farmers in Nebraska. Their names are on the back: Mom, Larry, Bud, Lally and Sis. Her mother asks if she’d like to live in America, and Sally, who’s only ever called her mother Teddie, asks would they be living with Mom, Larry, Bud, Lally and Sis?

Her grandmother runs a local lending library and complains that she can never keep copies of For The Term Of His Natural Life, which the Americans are always borrowing, but never returning, so she has to order more. When whispers begin of a move north, one young soldier asks her to mind his personal belongings – in the event, he says. She never sees him again, so she returns his things to the US Army.

Johnny Briggs gives her mother a pale blue, silk scarf showing a map of the Pacific with the islands heading north to Japan and after he’s gone, he sends her a telegram saying: MORE TO DIE FOR, code for Morotai Island, where he’s based, but she doesn’t understand it. He has asked her to mind his money while he’s away and to go for the war bride interview, where an American padre asks, ‘Do you have Aboriginal blood?’

Sally’s mother, with her neat, black bob and brown eyes, has never been asked this before and says, ‘That’s none of your business.’

He explains they must be careful, after huge race riots in Detroit in 1943, and again asks, ‘Do you have any Aboriginal blood?’

Again she says, ‘That’s none of your business.’

‘Then this interview is at an end,’ he concludes, after which she has to write to Johnny and send his money back to Army HQ.

One night, at bedtime, her mother lifts her up and says, ‘Look! Fairy lights!’ and where the night sky has been browned out and dark before, coloured lights now brighten the distance.

‘What are they?’ asks Sally.

‘It’s Kinneil, one of the grand old houses in the Cross where the officers stay. They must be having a party.’

Next day her grandmother is listening to the radio and suddenly starts shouting, ‘The War’s over! The War’s over!’ Then she’s running round the flat pulling down curtains and blinds, ripping blackout paper from the doors and Sally realises her secret fox will have gone.

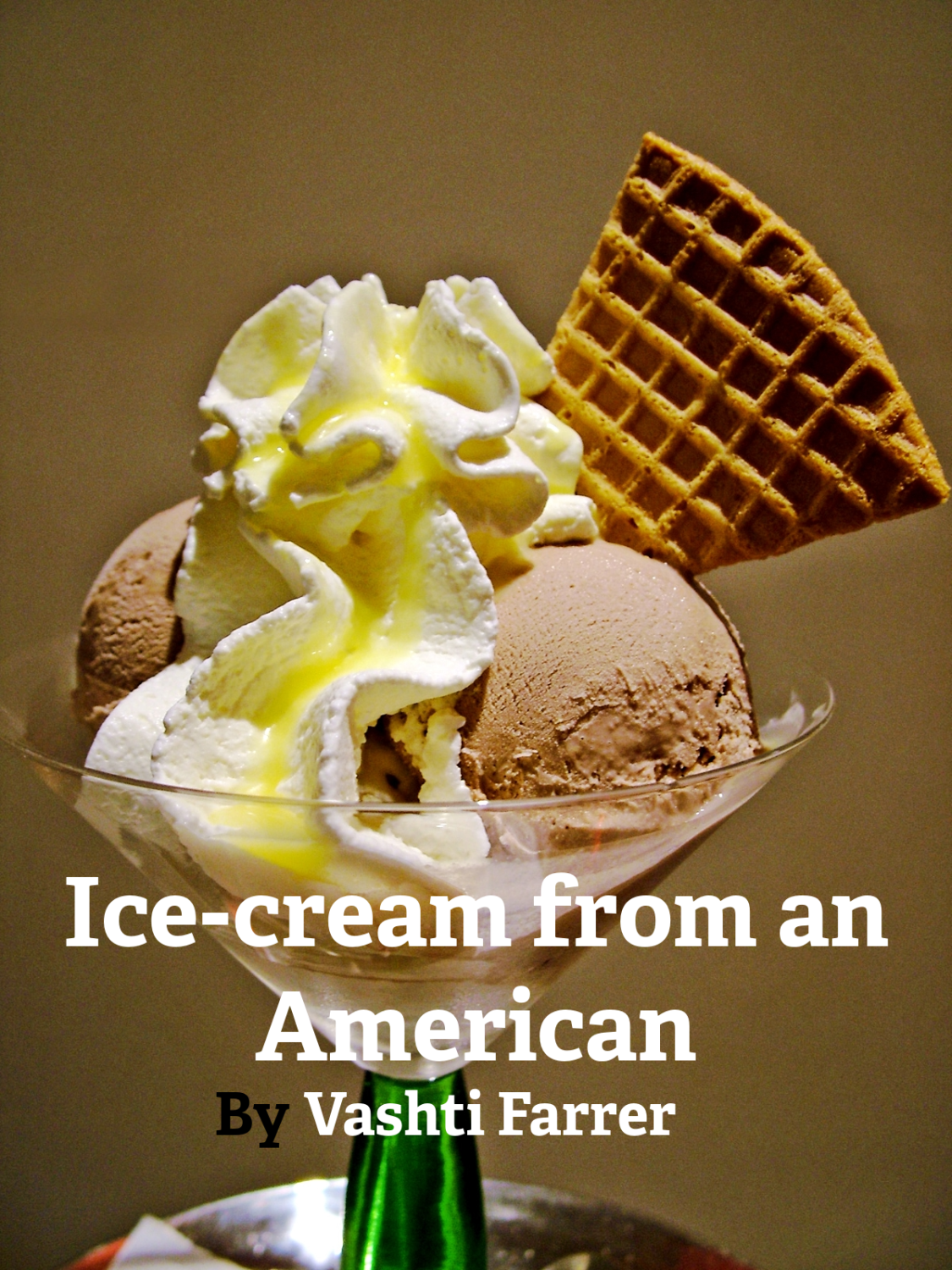

Next morning, she goes up the steps beside their building to see what the street looks like now the War is over and soon, an American in his smart uniform comes by. He stops and says, ‘Would you like an ice-cream, kid?’

Sally knows not to take lollies from strangers. But he’s not offering lollies and when he asks where he can buy one, she points to the little corner store nearby.

‘Wait here,’ he says. ‘I’ll be straight back.’ He sets out at a fast pace and is back within minutes and hands Sally the biggest ice-cream she’s ever seen – a double cone with two whole scoops! ‘It’s starting to melt, so lick it quick.’

Sally thanks him, and he’s gone. She comes back down the steps, licking her trophy.

‘Where did you get that ice-cream?’ demands her grandmother.

But somehow, her grandmother knows.