By Daniel Pernar

Echoes of men screamed in the silence.

Yet, these dreams don’t fool me yet.

No echo more, than an echoed violence—

And no violence more, could we have ever met.

Ivana wrapped her hands around Ante’s wrists. The proud woman now begged. ‘Please—please…don’t go—’

‘He has no one,’ said Ante, ‘I’ll be gone two, three days. I’ll be back. I—’

‘You can’t promise that.’ Ivana desperately tightened her grip. She risked wounding Ante.

‘I owe it to my brother,’ said Ante, ‘He must be restless, knowing his son rots alone.’

‘Your brother is dead!’ Ivana’s grip grew violent. ‘If you go, you will be too.’

Ivana—my Mama—was not a seer, and not a witch. Yet her prophetic warnings would come to life as ghosts. They haunt me.

Ivana’s eyes did not wander, even though her tears welled. ‘So many men have disappeared from Karlovac. You won’t be any different.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Ante, ‘You believe the rumours about Karlovac?’

‘If you leave us, I’ll curse you.’

Ante blinked at his wife’s eerie threat.

‘I’ll curse you!’ Ivana’s hold now bruising, her shackling grasp marking her husband’s forearm.

‘I love you, Ivana.’ Ante broke away from his wife’s hold. ‘You know I must go. I promise, I’ll be back.’

The memory returns each night, uninvited.

Always a loop, yet never a noose.

The vultures—they stole yet remain unindicted.

No justice; No alibi; No charmless excuse.

My brother’s calloused hands shook me awake. I shuddered, haunted by that recursive episode. It was the last conversation my parents would have in this life.

‘Zvonimir, wake up,’ said Vinko, ‘We need to leave soon if we want to make it to Letinac in time.’

‘Aren’t we in Lipice today?’ I asked.

‘The Žanićs stopped responding—I doubt it’s safe,’ said Vinko.

My brother clipped my head with an open hand to rouse my memory, or perhaps to vent his frustration. ‘The partizani, moron…did you want to meet the same end as Tata?’

My brother seemed unaffected by the phantom of our father’s death. I wonder how long his front would last.

Less than a month earlier, a villager from Karlovac travelled to Križpolje.

News was never good. The traveller’s grimace spoke before his words.

Forty men dead. All travelling to the zatvor to visit loved ones. Lined up like sheep. Ordered against the stone walls of the prison. They met a firing squad and a flurry of bullets.

Tata never returned. He lives now in the prayers of his children and the curses of his widow.

‘What farm are we going to?’ I asked.

‘Glasić.’

‘The ones that lost their son during the last round-up?’

A whimper travelled from the other side of the den where the six of us slept; a whimper that answered my question.

Zlata, our sister, watched us with wide-open eyes. Seldom did she speak anymore; we were all followed by ghosts. She was the most haunted.

Months before Tata’s passing, there were seven kids in the Draženović family.

Child-minding was women’s work. Be that a girl of six, or a woman of sixty. Zlata was only eleven, minding the infant Bruno.

A misstep.

A boiling pot of water.

There were now six Draženović children left to mourn their father’s death.

The morning cold doesn’t nip at the farmhand,

But on the road to nowhere did the violent winds stalk.

The farm passes time in our homeless homeland,

And so, on the road to nowhere, would the brothers walk.

‘I think I’ll marry a girl from Letinac,’ I said.

‘What do you have to offer a woman?’ said Vinko, ‘Those sack pants Mama stitched together?’

I couldn’t say when my brother grew so fickle about etiquette. Yet, I was glad only his words were cutting; Vinko threw an axe at Mama not yet a week ago. I guess it was her fault Tata was still dead.

It was our job to make money now. If we woke quietly in the night, Letinac was in reach. Hopefully we were paid in more than sustenance. Our farm had overgrown. Nobody could afford hemp anymore, not during the ongoing occupation.

I kicked a stone, barely promising an obstacle. ‘I just don’t want to marry a cousin.’

Vinko leered at me. ‘What if our cousins are the only ones that make it through this?’

‘What if there is no through this?’

‘We run.’

‘To where?’

Vinko slowed his pace to halt at the last house of Križpolje. ‘Through this. Somehow. Somewhere.’

Vinko turned to me. ‘Don’t grow attached. We’re not welcomed there; we’re not welcomed here.’

It seems we were both dreaming of destinies greater than our parents; to be more than the livestock we were bred to become. The poetics ceased when a familiar, nameless face hurdled through a front door.

‘Moje ljubavi!’ the figure spoke. It was the lone woman of the village, Vještica. I’m sure she had a name, but we only knew her as the witch. She bestowed her love to each child of the village, a rare commodity since kindness had grown sparse.

Through her dirt-trodden palms, she beckoned us to eat. ‘Jesti, Jesti!’

Two cubes of sugar. Exchanged for a moment upon the rising sun. The woman was unwed and unbred. I would never come to know how Vještica afforded food. I would not have to wonder for long.

We continued.

The hostile winds ensured the sugar would not sweeten our spirits. The long road and the surrounding forest became indistinguishable.

‘We’ll take a shortcut,’ said Vinko.

I furrowed my brow. ‘Shortcut? You’ve never been to Letinac—’

‘Straight through the woods.’

‘The forest stretches everywhere?’

Vinko let out a short breath. ‘Oh, you’ve explored the whole forest?

I pulled back my face. ‘No, I—’

‘Then it’s settled. After this hill, we don’t follow the bend round to Brinje,’ said Vinko, ‘We keep forward. Straight to Letinac!’

‘I don’t think—’

‘—or we go to Brinje, I sell you for some coins. Maybe a pig?’ Vinko couldn’t help but laugh through his threat. ‘Then I return home. A hard day’s work done. Mama would be happy she has one less mouth to feed.’

My mouth sat agape. It seems I lost this battle. I couldn’t throw a single punch.

The forest was vast. Lifeless. The trees slumped over one another, their roots entangled in a soil that wouldn’t feed them. They clung to the life they once lived.

The dead always lingered a little too long around these parts.

My feet never found footing in the woods. No balance. No grace. I wish I were a ghost and could float through the foliage.

Maybe that would be my calling in the next life.

The trees finally cleared into plain fields that gave way to scattered farmhouses. A church steeple cut through the horizon. There was a stillness that challenged the violent winds and the woods that carried us here.

Vinko smirked, hands on his hips. ‘Ah, Letinac.’

I wouldn’t lose this fight. ‘How could you possibly—’

‘Tata brought me here once,’ said Vinko.

I now had nothing to say.

Vinko’s grin escaped his face. ‘It’s how I knew the shortcut. The Glacić’s farm is the last one on the right. It’s quicker to walk through their pasture.’

We trekked carefully through their grassland. We tried not to spook their livestock.

Futile! Terror would soon make itself known.

Heavy were the feet that thumped over the calm—

To a door hung off its hinges;

To a blood-painted farm.

Heaviest was the hurry of hooves,

And the promise of violence,

Marched in a stillness that proves,

Brothers must pray in silence.

I was paralysed. Hooves hustled around the farmhouse. Shouts echoed across the fields. Death was approaching, and I would only have myself to blame.

Whilst considering my mortality, a single arm met my shoulder. I was wrenched deep into the underbrush.

‘Get down, budala!’ Vinko hissed through his teeth. ‘They haven’t seen us yet.’

I don’t think he was certain. However, crouched at the edge of the overrun pasture, I froze.

Silence was our only currency. We paid our pound of flesh with absence. The soldiers followed through Letinac. Their unruly shouts drowned the stillness of two peasant boys.

The invaders would soon meet Brinje. North to Križpolje. South to Prokike. We were gambling with the devil; time would pass us by regardless.

The hooves were no longer heavy; catatonia would no longer serve me. Our silence was paid.

‘We have to go,’ said Vinko.

I nodded. ‘We’ll follow the road north—’

Vinko clipped my head with another open palm. ‘We need to warn—’

‘Follow the danger?’ I interjected, ‘What use are we dead?’

‘And leave the village to die?’

‘No, I don’t—’

‘Fine.’ Vinko stood up, shaking the grass off his flannel. ‘I’m going back to Križpolje. I’m going home.’

‘I’m coming—’

Vinko put his hand on my shoulder. ‘You can run, but you can’t escape this, Zvonimir.’

I sighed.

‘If we die, Mama will resurrect us and kill us again,’ I said, ‘you’re willing to put her through that?’

Vinko sucked his lips behind his teeth. He wasn’t too stupid to ponder the consequences; he was too brave to believe we had any choice here.

I nodded.

Vinko nodded.

We sprinted along the road home. The noise was relentless. Our feet met loose pebbles that screeched when they scattered. The huff of our breath was no match for the returning winds. Trees, branches, and twigs barked judgements at our efforts to make it in time.

Make it where?

And in time for what?

I don’t think we knew.

The barrage of sounds failed to drown out the faint whispers. A tongue not understood. The lightness of hooves that trotted in the distance.

I hurried. My feet couldn’t match Vinko’s pace. My voice would reach him. My arms would not.

‘V-Vinko’, I huffed, ‘…Slow d-down!’

‘No time.’

‘…You’ll leave me behind?’

Vinko stopped. His face contorted into an enraged puzzle. His arm raised a flat hand. ‘We must make it. There’s danger—’

‘The danger is coming this way.’

‘You’re stupid.’

I gestured to the shortcut that would lead us straight to Križpolje. ‘Let’s hide here…just, trust me for now?’

Vinko chuckled, ‘Don’t be a coward.’

‘Be foolish, like Tata?’

Vinko’s arm moved at a pace my eyes couldn’t follow. The kind of pace that would stop an infant from falling into a pot of boiling water.

My anger dulled the echoing sting of my cheek.

Vinko bit his bottom lip. His eyes wider than the road behind us. ‘You forget your place.’

I shoved my brother in the chest. Not enough force to start a fight. Enough to say I noticed.

I flung up my short arms, as far as they would go. ‘Just here, behind these shrubs—I told you; we’re no good dead.’

‘We’re not gonna d—’

‘That’s what Tata said.’ I locked eyes with Vinko. His expression shifted, looking for an excuse.

‘Fine.’

‘Is violence always the—’

‘You’ve wasted enough time, kurac.’

I couldn’t see how this was my fault, but my anger was fading. The ache of my cheek makes itself known. I didn’t need another swifthanded reminder.

We moved left into the forest. Our tiny bodies hidden behind dead shrubbery and weeds. It had only been a moment, yet Vinko was out of patience.

‘We don’t have time to—’

I slowly put my hand on his shoulder, trying to drag him down to my level. The foreign tongue was growing louder. The hooves heavier. Silence became virtue once again.

In minutes, moments, or maybe hours, a small slew of soldiers trotted by our recluse. Even breath was too loud. Between suffocation and the cold, our olive skin grew purple.

Six men stopped before us.

Talijanski.

Partizani.

Their bellies sagged like sacks. They grunted like swine at a trough. Their horses may have alerted them to the two peasants. The two witnesses. But perhaps they were distracted, burdened too cruelly by their load.

The soldiers stopped, chatting only a few paces away. Ambivalent. Unaware of their villainy. They would be paid regardless. I don’t think they got a bounty for every peasant slain, but I wonder how much two children would fetch them.

The cruel winds became hushed. We were now forced into voyeurism. Ironic. We’re bred as livestock and still hold theatre with pigs. Yet, both booing and applause would result in execution. We just witnessed.

And continued to witness.

An eternity passed, the soldiers moved onward, returning to the scene of their crime. Chatter became babble. They moved beyond the horizon.

Vinko let out a breath: long, overdue, relieved. I worried he would pass out.

‘The forest. Now!’

In a fluid motion, we turned and ran through the maze of trunks, roots and weeds.

Our sprint became a hurdle. Dodging twisted beeches and gnarled spruces. Winter had eaten the trees. It would be months before they would be born again. It would be about forty minutes to Križpolje.

We had no time for either.

The forest ended along the lone road. The bend to Brinje lay ahead.

The winds chilled, yet our legs were on fire. Our hearts raced faster. We could see the first house on the horizon. The one that gifts sugar.

Vještica!

She wasn’t blood but might know something. Was Mama okay? Did the partizanski make their presence known?

Through the heat and the pain, we gained ground on the witch’s shack.

Why did the whole village surround it?

Peasants. Tears. A lone child holding a rosary—screaming to the sky; screaming to a God that wouldn’t listen.

Why did this unwed woman finally hold ceremony?

I imagine they smiled while she burned.

The pig who eats pigs, does he call himself cannibal?

Or in the kingdom of pigs, does he call himself king?

Is complicity not the burden of the misbehaved animal,

Who smiles at the filth, they so recklessly fling?

Vještica was made spectacle. Surrounded by whimpering women and men too proud, perhaps too cowardly to cry.

Across the crowd stood Mama, shaking her head, her mouth drawn into a thin line.

No tears. Just acceptance.

A hysterical Zlata knelt beside her. Her hands clutched to a rosary. Her palms charred on the surface. God himself rejected her intervention.

Zlata tried again to undo the wrong.

Zlata was again a moment too late.

The crowd circled the monument in the middle.

A roughly made fire: stones, sticks, and kindling. Tossed across the road haphazardly. It reeked both metallic, and of gasoline.

Two metal frames sat at the corners of the unstructured firepit. Crude scaffolding that supported the pyre. A long, rust-flaked, iron spike lay on top of the two mounts.

At its middle, the spike pierced a large sack of meat. Stripped of its clothing. Cooking like aged pork.

Vještica was spit-roasted. Alive.

Her body exceeded well-done and was now overcooked.

Yet, the pigs feast on her suffering and not her body. They laid her bare, only to be witnessed by the livestock she was confined with.

And the cruellest of all?

They had no clue, no idea she was unwed, unbred, and yet beloved. Her roasting corpse not a wound to any one man. Instead, a pulse that rippled through all Križpolje. Through each terrified witness.

I left Vinko to find Mama. The six-foot woman stood stern in her stoicism.

‘Šuti, ljubavi,’ said Mama, ‘Šuti!’

Being told to shut up twice was a plea, not a command. Mama hid behind a mask that refused defeat. I would not dismantle that.

So, I nodded.

The wicked theatre ruptured the village, yet sounded quite calm. Besides the ignored wails of Zlata, the crackle of the fire was the only constant.

But even the flames grew mute. A heaviness, a plurality was approaching.

The Hustle of hooves. The screech of obscenity. Turmoil neared the horizon.

Violent, foreign tongues challenged the mourning of the village.

Every Croat scattered. Like sheep without shepherd. Scurrying to get away from any horse or soldier, and the decrepit wagon that followed them.

A round-up!

I lost sight of both Mama and Vinko. Yet, Zlata remained begging for repentance.

She couldn’t afford to be too late. Not this time.

I yanked her shoulder, almost out of its socket. I rushed us both into Vještica’s shack.

‘Dovoljno!’ Zlata said.

But it wasn’t enough. Zlata couldn’t fall victim to circumstances once more. Too late would be never again. I couldn’t risk losing someone else.

I dragged Zlata into Vještica’s kitchen. Her pantry full of donations—I assume—sugar, flour, and eggs she couldn’t have worked for.

I placed my hand on Zlata’s shoulder and lowered her to the floor. She reached her charred palms outward to stop me. Her face was swollen. ‘It’s all my fault. Bruno, Tata, Vještica. I couldn’t save them. Please! Just let me die.’

‘Šuti!’ I said, ‘What will their deaths mean if you don’t make it—’

‘Maybe they’ll stop haunting me; maybe I’ll be able to sleep again.’

I was momentarily confronted with my sister’s confession, but only for a moment. We didn’t have time to continue the performance. I dragged a bag of flour in front of her body and shut the pantry door.

The foreign shouts echoed around the shack. At times they felt close. At times only distant murmurs. A loud thud flung the front door open. I had to hide. Not well. Not perfectly. But quickly. Quietly.

I crawled beneath the kitchen table and lay flat. The thuds became thunder that stomped through the small hovel.

If I moved, they would see me.

If I breathed, they would hear me.

If I bled, they would taste me.

So, in stillness, I remained. If silence were my currency, I would soon be in debt.

The thunderous footsteps roared the loudest they’d been yet. They were in the kitchen with us. I heard the pantry scrape open. A creaking, slow death.

And then, silence.

Had Zlata been caught?

Poor, tortured Zlata. Always a moment too late. A second from safety. A hand that just misses salvation. Yet, she didn’t lose this time.

I did.

My feet were dragged out from under me. A bastard tongue screaming words that didn’t quite land. Even if I understood them, would I care what they said?

It was a flurry of movement. I kicked. I scratched. I bit down on air. Held tight over a soldier’s shoulder, a trapped lamb that pigs found in the dark.

I screamed for someone—anyone to listen. ‘Pomoć!’ But nobody dared help.

I begged. I pleaded. With the soldiers. With the village. With God. But my prayers remained unanswered.

Thrown into the wagon, two, maybe three faces surrounded me. They had already accepted their fate. I could not.

I scratched at the floor. I tried to pounce out the back door. My forehead met with the buttstock of the gun.

God was dead.

If he was alive, he was cruel.

Cruel enough to give power to pigs, but not their playthings.

Like any other round-up, I knew where this wagon would go. My chances of survival there were much slimmer than they were here. If God were listening, I hope he’d respond this time.

The wagon mocked us, chanting hymns to its cargo.

Come one and come all to the executioner’s ball!

The wagon will guide you to the prisoner’s hall.

Will a single misstep see your downfall?

Or will you be the one, the devil may call?

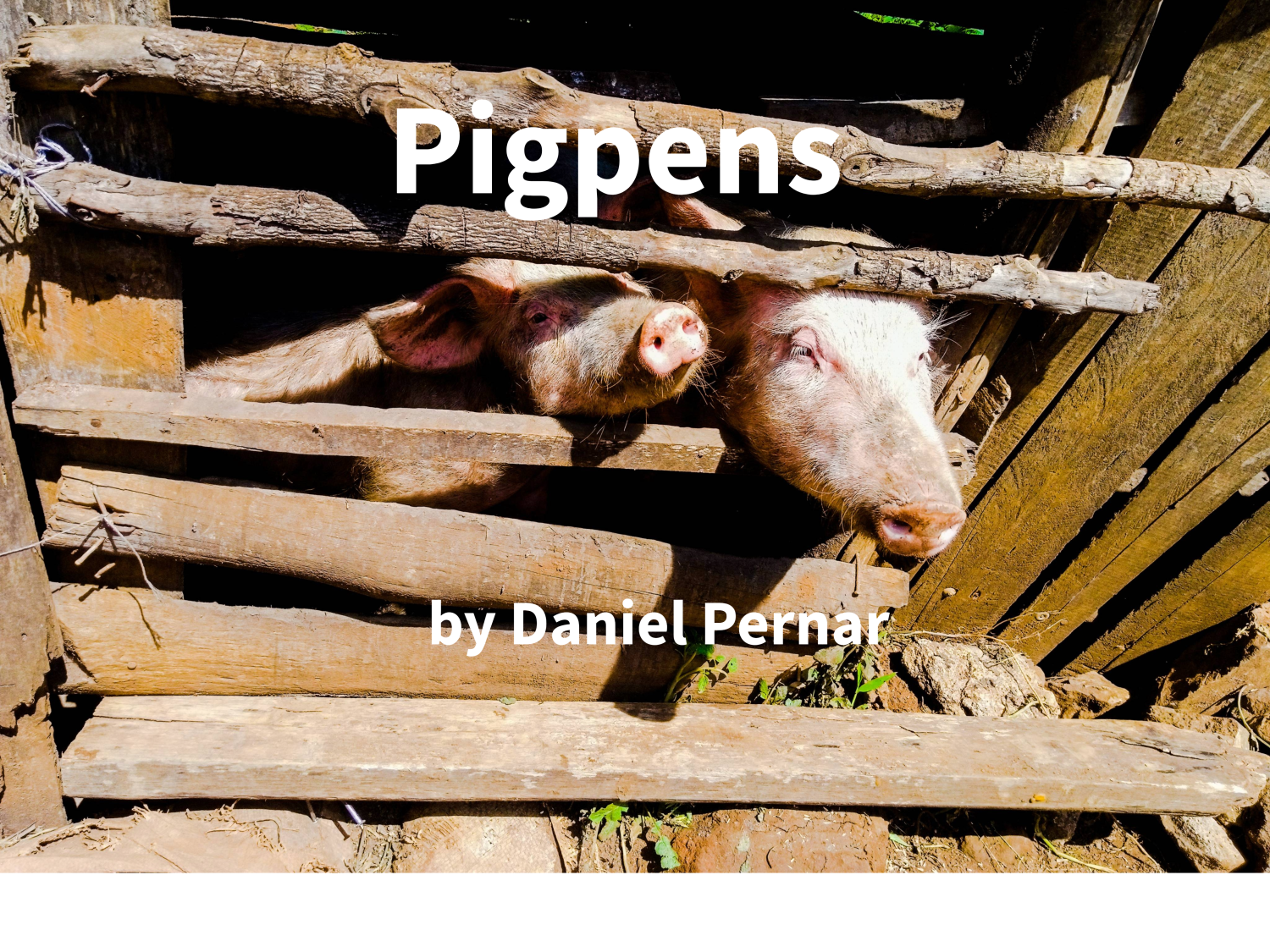

It was both routine and random. We all marched into the pigpen: a prison. A holding cell for the ill-bred and the inbred. Farmers forced to live as livestock.

I joined the rest of the damned in a foyer of sorts. I had never been to this prison. It was as rotten as any other.

I scoped the room, blessed that my nine-year-old head didn’t rise above the adults I was trapped with. I couldn’t run the risk of being seen; I couldn’t run the risk of becoming unblessed.

My siblings weren’t here. Slava Bogu!

A woman across the hall was less covert; her wailing baby brazenly increased to a roar.

A soldier ushered for the child’s silence, a fabricated act of distorted humanity.

‘Please.’ The woman wept. ‘Let me feed him!’

‘Shut him up,’ said the Soldier, ‘or I will.’

‘It’ll just be a—’

The soldier jerked the infant from his mother’s arms. In a swift motion, the child’s head divorced from his body. The soldier threw the detached appendage to its owner.

‘You can feed him now, Svinje.’

Too late, was never again.

Another one to linger.

How long would he haunt his poor mother?

His cries, his shrieks, looped in her dream forevermore.

Not ever replaced, not with sister, nor brother,

When almost forgotten, he chants ‘nevermore.’

Unless we all died here, for that I could yearn,

And not have to bear witness to the unending slaughter.

Each cruel vision burnt, I could never unlearn,

That pigs will drink blood, before they drink water.