The A4 Interstellar Quarterly

Galactic News

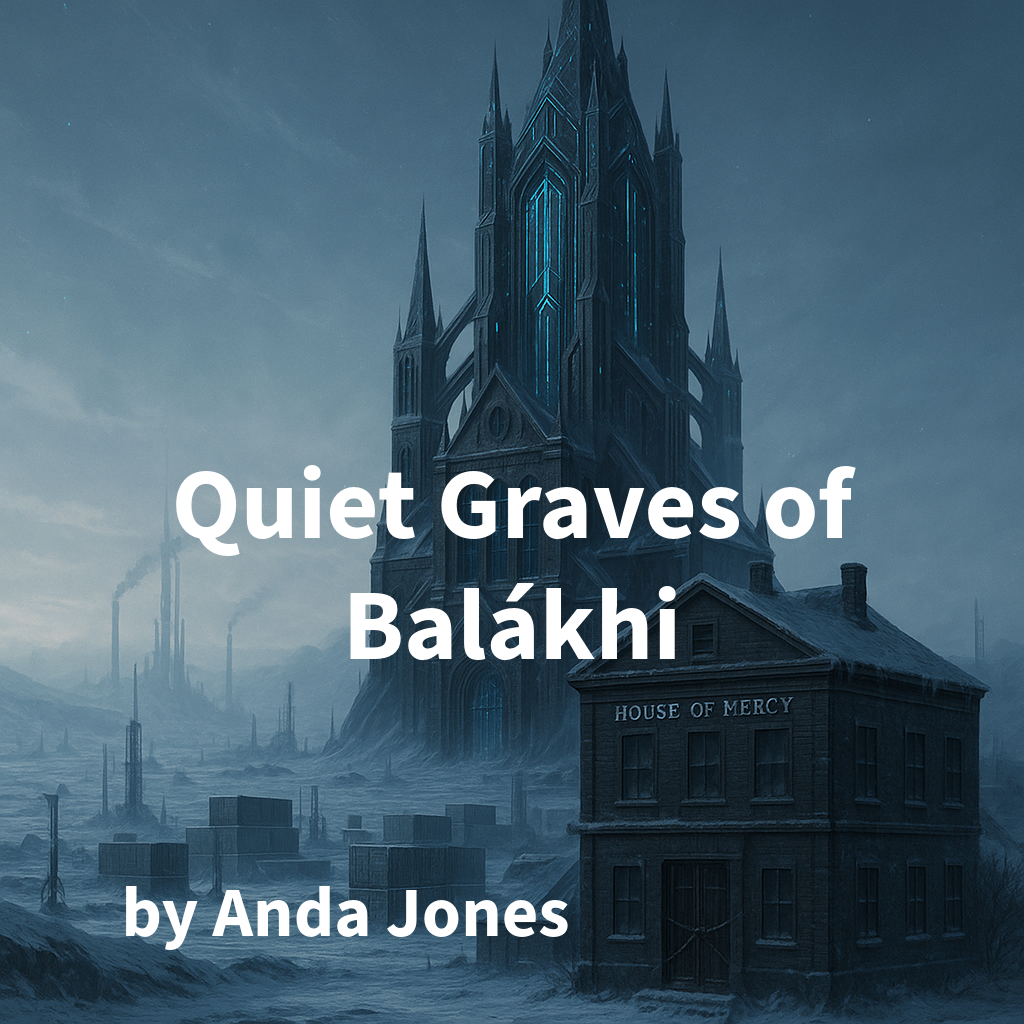

Quiet Graves of Balákhi

by Anda Jones

15th Quater 8563

I bring sweet Martian biscuits to meet Margot Hedtesa. As the son of a Balákhi woman, I know good conversation requires tea, and tea calls for biscuits. Margot is a reserved woman, but with each visit—and each box of biscuits—she reveals a little more of her motivations in uncovering the ghosts of the House of Mercy.

My journey takes me to the icy colony of Balákhi (pronounced Bal-Ark-Ey), the proud seat of a Khánon archdiocese. The town’s backbone is its skyscraping cathedral. It looms over frosted fields, industrious drills and the ephemeral skyline of colossal, star-bound shipping containers.

Around the corner from the cathedral stands the derelict House of Mercy. Once it housed approximately 70 mothers and over 150 children. Managed by the Khánon and financed by the government, it depended on the deep relationship between the dominant religion and fledgling star system.

Painfully small windows overlook the soot-specked, snow-covered street. Only furtive ghosts peer from those windows now. Echoes of the Benía Sisters stride empty corridors, keeping watch over their charges. Sinners and their illegitimate spawn. The fallen.

‘Those were the Devil’s children,’ former school principal, Harold Báro says, ‘that’s what we were taught.’

As a schoolgirl, Margot Hedtesa often walked past the House of Mercy on her way to school. Her father taught her to keep her distance, her mother said nothing. Margot remembers watching in morbid fascination as the unholy devil spawn stumbled late into the classroom every morning. Margot was unsettled by their sunken faces, uneven haircuts and ill-fitting clothes as they shuffled past her desk to the back of the room. Good, respectable children kept their distance because the Mercy children did strange things: cried for no reason; slept at their desks; stole lunches or toys; called out ‘mummy’ and ‘daddy’ to complete strangers on the street.

One day, to get some hard-earned respect from her classmates, Margot acted out an old schoolyard prank. She took an empty candy wrapper, filled it with dirt, and presented it to a sickly little Mercy girl, Prudence Galdía. Prudence meekly accepted and eagerly unwrapped her unexpected gift, watched covertly by a snickering crowd. Margot watched as the little girl opened the wrapper to reveal its contents: a small handful of dirt. Her smile broke. The other children laughed as Prudence stumbled away, tears of exhausted shame hidden behind her hands.

This is the last time anyone will see Prudence Galdía.

At 63, Margot is a retired historian and grandmother to two healthy babies. Her smile is not easily given and any fealty to the Khánon is long since lost. Holoarticles and datapads from the Registration Office and Planetary Library mingle on the dining table. Quaint paper-written notes in Margot’s precise hand spill out of old-fashioned binders. The biscuits are perched, somewhat neglected, as Margot speaks to me in a soft but self-assured voice.

‘The dead live in Balákhi.’

A brutal, unstable climate batters the planet relentlessly. Deadly cold snaps can—and have—ended families in their homes. Walking hand in hand, religion and death run deep in Balákhi culture. Khánon funerals are public affairs. The dead are called thrice: a sounding of names, a call of affection, an offering of memories. To cut ties is to ‘never give your ghost another word.’ A wry Balákhi wedding proposal is ‘Will you do me the honour of haunting my family?’

‘My khalda set a lampfire and whiskey on the doorstep every Hallow’s Eve,’ Margot recalls, ‘kept a list of names for the last round.’

Tombstones are cleared of ice each morning with a reverent sounding of names. Communities gather for death. They share stories. Share drinks. Dead voices whisper between living ones along streets lined at night with fiery will-o-wisps. Did these stories drive Margot to uncover The House of Mercy’s secrets?

‘Perhaps,’ Margot explains, ‘My birbi’s funeral was quiet. Too quiet. Lots of faces. But no one had any stories to tell about her. I had nothing to say.’

I’m hungry for more, but we’ve concluded our biscuits for today.

That night, the pub windows glow orange on the glossy snow. I’m told it’s frequently packed and lively. The walls are covered by photographs. It’s a place where both living and dead enjoy moments of happiness, companionship and contentment. Drinks are poured out in memory—in celebration. Amongst it all, Marylin Armakh laughs. She offers me a drink and a wry grin as I sit.

‘Can’t tell a ghost story without a drink,’ she says.

Marylin’s deliveries took her to the House of Mercy’s greying steps many years ago. As she talks about the House of Mercy, her laughter fades.

’An awful old box,’ recalls Marylin.

Abortion was illegal in outlying star systems where religion was the first voice to take root. Pregnancy out of wedlock precluded legal access to welfare, housing, and meant ostracisation. Imagine a girl in a Khánon system. Impregnated by a man, sometimes a relative, who assumed neither shame nor responsibility. She could flee her shame alone or be received at the House of Mercy.

There, you rose before the sun to confess your sins. At first light, you were allowed into the nursery for breastfeeding and to change your infant’s diapers. Mass at 8, followed by hard grittle and whey for breakfast. Then you worked. Washing, packing, sewing, cleaning or whatever was required. Good hard service, the Sisters said, redeems you. You had short breaks to breastfeed. By the end of the day, you ate whatever the Sisters could provide. Before you could sleep, you were to repent and beg for forgiveness.

‘The girls—the mothers—cried,’ Marylin says, ‘we could hear it through the doors, or see it in their faces when we delivered the grittle.’

The institutional and social damnation was so strong, most mothers had nothing more than the Sisters’ relative charity. Life with the Benía Sisters was better than death under a blanket of snow. But the House of Mercy was only momentary salvation. Mothers awaited the inevitable day they were cast out—without warning, without money and almost always without their baby.

‘I hate it when people say those birbis abandoned their babies,’ Marylin says, ‘I knew a fallen birbi who came to Mercy every day, asking for her baby.’

In the name of facilitating adoption, Benía Sisters were instructed to tell mothers that, by seeking help, they had already relinquished their baby. In some cases, they gaslit mothers into believing this was a kindness; they were unfit to parent or their child was too unruly to handle. A Commission Inquiry revealed on three separate occasions that, when a mother was especially persistent, she was told her living baby had died.

‘The Sisters ignored that woman,’ Marylin says, ‘shut the door in her face, called the police, dragged her screaming from the steps. But she came back, every day, until she died on those freezing steps.’

The fallen children were stripped of their birth name and given a Khánon name. If the children tried to escape, the local police caught and returned them without investigation. One officer’s report reads: ‘female Khánon-raised child [redacted] found 14:30hrs at 11 Brákhi Road, West Hedrí. Minor bruising to arms and face; source unknown. Returned to the House of Mercy with instruction to eat and seek medical care.’ That was the end of the file.

When I returned to talk with Margot, I tried to put myself in her position. Why did her mother’s funeral bring the secrets of the House of Mercy?

‘Instinct,’ Margot says.

Margot’s mother died leaving many secrets. There was a heaviness that fell into place when Margot came across her mother’s birth certificate. In the space for the father’s name: nothing.

Her mother was born out of wedlock.

‘She kept it a secret,’ Margot says, ‘went through all of it and she was ashamed…’

Margot began to reevaluate all those fallen children in her memories. ‘I didn’t think much of them then,’ Margot says, ‘now I see my mother with them. I hear her, calling out to the strangers, crying… clutching an empty candy wrapper.’

We didn’t finish our biscuits today.

What became of the House of Mercy? In 8543, a cold snap struck, leaving Balákhi icelocked for 2 years. Unable to receive transport through endless hail and record-breaking winds, the frozen Balákhi starved. Its economy was devastated. When the ice retreated, the Benía Sisters moved across the system, leaving the House of Mercy’s doors permanently shut behind them. The padlock dangling from heavy chains stayed untouched many years until Margot Hedtesa.

‘Something in the house was calling me. I think it was my birbi,’ Margot explains.

Margot put her rusty history skills to use looking for the lost little girl from her childhood.

’There was an iced-over tombstone in the courtyard,’ Margot says, ‘but the Sisters didn’t put it there. They only conducted funerals at the cemetery.’

Margot asked around to see if townsfolk could provide her with a lead.

‘I wanted to figure out who put it there,’ she says, ‘It felt quiet somehow.’

This is when she uncovered the story of Brackly Grithná and Peter Mikhál.

Many years ago, 14-year-old Brackly and Peter climbed over the wall for a bit of mischief. They found a large concrete slab in the southwest corner that echoed underfoot. Expecting to find a basement, they heaved the slab aside to reveal a shallow, tank-like structure. At first, they were curious, perching on the edge, throwing stones in. Then, Peter nudged Brackly, causing him to fall. Lying at the bottom, Brackly realised that the floor of the structure was covered with a tangle of skulls and bones.

Understandably shaken, they ran down the street to get Peter’s mother, Janette. After some convincing, she agreed to accompany them back to the bones. Horrified, Janette Mikhál called the police.

Even all these years later, Janette shakes as she recounts her story for me.

‘These look small. Really small. Like children,’ she told the police.

‘Probably stillborns,’ they told her. ‘They’d be unbaptised. So, the Sisters wouldn’t bury them in holy ground.’

The police directed her to the council. The council directed her to the Khánon, who directed her back to the council, and so on. After several hours of bureaucratic hot potato, Janette gave up. She headed to the cathedral, requested an unnamed tombstone and the services of a priest. A moderate expense and a few curt responses to the council later, a Khánon funeral was held. It was quiet. Too quiet. Attended by only the two boys and their parents, there was nothing to say. And that was that. The tombstone lay forgotten. No one left a lampfire on All Hallow’s Eve. No one cleared the ice. No one sounded the names of the dead.

It stayed that way for 60 years. Until, one day, Margot brought her notebook to record the boys’ story.

‘That story started it. The thread that unravelled the whole thing. I’m still pulling it, unravelling it,’ she says, indicating her copious handwritten notes, ‘I wished I’d thought to use a datapad.’

Following the story, she buried herself in the Planetary Library and searched the location with every map she could find. Eventually, she found something. The structure was a decommissioned sepsis tank. A nasty suspicion arose.

Margot headed to the Balákhi Registration Office and requested all cemetery intakes. From there, she painstakingly cross-referenced by hand the intakes with the Benía Sisters’ records. The tedious work paid off. Nearly 473 baptised infants’ remains were unaccounted for. Margot published her findings in the local newspaper and braced for backlash. None came.

‘No-one cared. Not when they were alive. Not when they died. All for something that wasn’t even their fault.’

Margot kept digging. All illegitimate children who died in the care of the Benía Sisters at the House of Mercy had been denied a proper burial. The little bodies were thrown in a sewer, for fear they would corrupt the hallowed ground in the cemetery. And the causes of death for these fallen children were many. Broadly the most common were disease, malnutrition, exposure, and improper medical care.

‘One little boy had gangrene,’ Margot recounts, ‘the smell was so bad, the children along the hall complained to the Sisters. A doctor was called but it was too late. He’d already died.’

She sent her complied findings to the B6 System Times. This time they took notice.

Politicians, the Khánon, journalists. For months, there was uproar. Margot was swept up by the outcry. But eventually, finally, came the infamous Interstellar Human Rights Commission: ‘The Lost Children of Balákhi.’

‘Finally,’ Margot says, ‘I could hear their voices. Finally, they were remembered.’

Of the staggering total 974 missing, 913 children’s bodies were discovered in the House of Mercy sewer. Then, began the long process of excavation and identification. Now, the children are buried under their own names in hallowed ground at a memorial site in Balákhi.

Margot still scours the pages of the Commission hoping to find one name. Prudence Galdía.

‘I’d like to bring a lampfire for her on Hallow’s Eve. It’s the least I could do,’ Margot says.